– Text / Tekst in: Deutsch English Polski –

[DE] Die Witwe Matrena Popel war 71 Jahre alt, als die Deutschen die Erdölstadt Boryslaw besetzten. Sie lebte in bescheidenen Verhältnissen, hatte einen Garten und eine kleine Landwirtschaft. Mit ihr im Haus lebten ihr Sohn Vasili und ihre Schwiegertochter Stefania. Vasili war Priester der griechisch-katholischen Kirche: einer Kirche mit orthodoxem Ritus, aber dem Papst als Oberhaupt, die auch verheiratete Männer als Priester zulässt. Vasilis Frau Stefania war eine junge Kindergärtnerin.

read more / Czytaj więcej >

Zu ihren Nachbarn gehörte die dreiköpfige jüdische Familie Lippman: Abraham Lippman (Bauunternehmer und Sägewerksbesitzer), seine Frau Etka und ihr damals zehnjähriger Sohn Józef. Stefania und Etka waren befreundet. Als die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Juden in Boryslaw begann, mussten sich die Popels entscheiden, ob sie unter eigener Lebensgefahr ihren Nachbarn helfen und sie verstecken sollten. Sie entschieden dies gemeinsam – aus menschlichem Anstand, aus Freundschaft und aus christlicher Überzeugung.

Vasili wurde nach dem Krieg als Angehöriger der griechisch-katholischen Kirche verfolgt und zu Zwangsarbeit in Sibirien verurteilt. Er kam nach Kolyma – einem System von Arbeitslagern im Gebiet des Flusses Kolyma in Ostsibirien. Hunderttausende mussten dort bei arktischer Kälte unter unmenschlichen Bedingungen Zwangsarbeit leisten: über und unter Tage beim Goldschürfen, bei der Suche nach Zinn und Uran, beim Straßenbau, beim Holzfällen. Solschenizyn beginnt seinen autobiographischen Bericht „Archipel Gulag“ mit einem Prolog zu Kolyma. Nach Stalins Tod fiel Vasili unter eine Amnestie, aber war kein freier Mensch. Er musste in Kasachstan arbeiten, bis er endlich, als gebrochener Mann, 1957 zu seiner Familie zurückkehren konnte. Seine Frau Stefania verlor als Frau eines „Volksfeindes“ ihre Stelle als Leiterin eines Kindergartens. Auch nach dem „Tauwetter“ unter Chruschtschow wurden sie nicht rehabilitiert, sondern weiter ausgegrenzt, verdächtigt und benachteiligt. Nur mit Gelegenheitsarbeiten und den Erträgen aus ihrem Garten und der kleinen Landwirtschaft konnten sie überleben.

Die Rettung von Juden war wie der Holocaust selbst aus innen- und außenpolitischen Gründen ein Thema, das in der Sowjetunion weitestgehend tabuisiert wurde. Ihre 1943 geborene Tochter Orysia erfuhr das erste Mal nach der Rückkehr ihres Vaters, dass ihre Eltern Juden gerettet hatten.

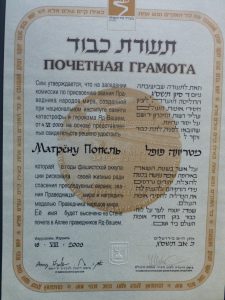

Matrena, Vasili und Stefania waren bereits mehrere Jahre tot, als Yad Vashem ihnen 2003 posthum die Ehrung als „Gerechte unter den Völkern“ zuerkannte.

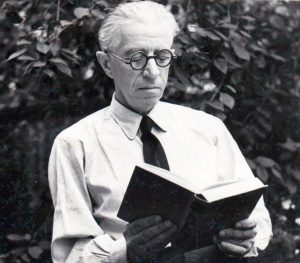

Kurzbiographie Matrena Popel

Kurzbiographie Vasili Popel

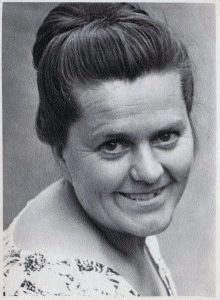

Kurzbiographie Stefania Popel

[EN] The widow Matrena Popel was 71 years old when the Germans occupied the oil town of Boryslaw. She lived in modest circumstances, had a garden and a small farm. With her in the house lived her son Vasili and her daughter-in-law Stefania. Vasili was a priest of the Greek Catholic Church: a church with Orthodox rite, but with the Pope as its head, allowing married men as priests. Vasili’s wife Stefania was a young kindergarten teacher.

Among their neighbours was the three-member Jewish Lippman family: Abraham Lippman (building contractor and sawmill owner), his wife Etka and their then ten-year-old son Józef. Stefania and Etka were friends. When the persecution and murder of the Jews in Boryslaw began, the Popels had to decide whether, at the risk of their own lives, they should help their neighbours and hide them. They decided this together – out of human decency, friendship and Christian conviction.

Vasili was persecuted after the war as a member of the Greek Catholic Church and sentenced to forced labour in Siberia. He was sent to Kolyma – a system of labour camps in the Kolyma River region of Eastern Siberia. Hundreds of thousands were forced to work there in the Arctic cold under inhumane conditions: above and below ground in gold mining, in the search for tin and uranium, in road construction, in logging. Solzhenitsyn begins his autobiographical report „Archipelago Gulag“ with a prologue to Kolyma. After Stalin’s death, Vasili fell under an amnesty, but was not a free man. He had to work in Kazakhstan until finally, as a broken man, he was able to return to his family in 1957. His wife Stefania, the wife of an “enemy of the people”, lost her job as head of a kindergarten. Even after the „thaw“ under Khrushchev, they were not rehabilitated, but continued to be marginalized, suspected and disadvantaged. They could only survive with casual work and the income from their garden and small farming.

Like the Holocaust itself, the rescue of Jews was a topic that was largely taboo in the Soviet Union for reasons of domestic and foreign policy. Her daughter Orysia, born in 1943, was the first to learn after her father’s return that her parents had rescued Jews.

Matrena, Vasili and Stefania had already been dead for several years when Yad Vashem awarded them posthumous honors as „Righteous among the Nations“ in 2003.

Short biography Matrena Popel

Short biography Vasili Popel

Short biography Stefania Popel

[PL] Wdowa Matrena Popel miała 71 lat, gdy Niemcy zajęli miasto ropy naftowej Borysław. Mieszkała w skromnych warunkach, miała ogród i małe gospodarstwo rolne. Z nią w domu mieszkał jej syn Wasilij i synowa Stefania. Wasilij był kapłanem kościoła greckokatolickiego: kościoła z obrządkiem prawosławnym z papieżem jako głową kościoła i żonatymi mężczyznami jako księżmi. Żona Wasilija, Stefania, była młodą nauczycielką w przedszkolu.

Wśród ich sąsiadów była trzyosobowa żydowska rodzina Lippmanów: Abraham Lippman (przedsiębiorca budowlany i właściciel tartaku), jego żona Etka oraz ich wtedy dziesięcioletni syn Józef. Stefania i Etka były przyjaciółkami. Kiedy zaczęły się prześladowania i mordowanie Żydów w Borysławiu, Popelowie musieli zdecydować, czy z narażeniem własnego życia powinni pomóc sąsiadom i ukryć ich. Zdecydowali o tym wspólnie – z ludzkiej przyzwoitości, przyjaźni i chrześcijańskiego przekonania.

Po wojnie Wasilij był prześladowany jako członek Kościoła Greckokatolickiego i skazany na pracę przymusową na Syberii. Został wysłany na Kołymę – systemu obozów pracy w rejonie rzeki Kołymy na Syberii Wschodniej. Setki tysięcy ludzi zostało zmuszonych do pracy w arktycznym mrozie w nieludzkich warunkach: nad i pod ziemią przy wydobyciu złota, w poszukiwaniu cyny i uranu, przy budowie dróg, przy wycince drzew. Sołżenicyn rozpoczyna swój autobiograficzny raport „Archipelag Gułag“ prologiem do Kołymy. Po śmierci Stalina, Wasilij został objęty amnestią, ale nie był wolnym człowiekiem. Musiał pracować w Kazachstanie, aż w końcu, jako złamany człowiek, mógł wrócić do rodziny w 1957 roku. Jego żona Stefania, żona „wroga ludu”, straciła pracę jako kierowniczka przedszkola. Nawet po „odwilży“ za Chruszczowa nie zostali zrehabilitowani, ale nadal byli marginalizowani, podejrzani i pokrzywdzeni. Mogli przetrwać tylko dzięki dorywczej pracy i dochodom z własnego ogrodu i drobnego rolnictwa.

Podobnie jak sam Holokaust, ratowanie Żydów było w Związku Radzieckim tematem, który ze względu na politykę wewnętrzną i zagraniczną był w dużej mierze tematem tabu. Ich córka Orysia, urodzona w 1943 roku, jako pierwsza po powrocie ojca dowiedziała się, że jej rodzice ratowali Żydów.

Matrena, Wasilij i Stefania nie żyli już od kilku lat, kiedy w 2003 roku Yad Vashem przyznał im pośmiertnie tytuł „Sprawiedliwych wśród Narodów Świata“.

Krótka biografia Matreny Popel

Krótka biografia Vasilija Popela

Krótka biografia Stefanii Popel

Sources: Yad Vashem Righteous database, M.31.2/9968/1; Kappeler, Geschichte der Ukraine; Snyder, Black Earth; Lipman, Memories

Photos: Private archive family Popel and descendants (5), wikimedia commons cc (2), Hasbron-Blume (3)

Schreibe einen Kommentar