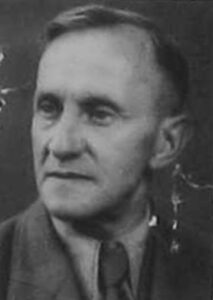

[EN] The Alexander Goldwasser family

Alexander Goldwasser was born in 1883 in Krakow and graduated as a civil engineer from the University of Lviv in 1911. Like many Galician Jews, he venerated the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, who had granted civil liberties to the Jews. Before beginning his studies, Alexander had served a voluntary year in the military. During the First World War he was posted to the Italian front for two years and then to the military construction department in Krakow. After the war Alexander founded a family with the ten years younger Regina Renia Mangel from Zakopane: on 15.01.1920 his son Marcel was born, on 27.03.1921 his daughter Dola. From 1919 on, Alexander Goldwasser built up an existence as an independent civil engineer in Drohobycz. He was a respected, socially committed member of the Jewish community and urban society. Jews were not treated in the Municipal Hospital; the pre-war Jewish hospital was in a desolate condition and was about to close. Alexander Goldwasser was elected to the committee which, after four years of hard work, successfully managed the reconstruction of the hospital.

read more >

“Central heating was installed, twenty beds were added, and proper equipment was provided. In the fall of 1938, the hospital was returned to the Jewish community. It was designed by the engineer Goldwasser, who also directed the building’s renovation from start to finish.” (Rothenberg, https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/drohobycz/dro095.html)

Goldwasser’s children were healthy, hard-working and intelligent. His son Marcel studied in Lemberg from 1935. Under the circumstances of the time, the Goldwassers were a happy family in secure conditions, living in the centre of Drohobycz at Markthallengasse 2 (uliczka Hali Targowej). Their situation only changed abruptly with the Soviet occupation in 1939: as a „bourgeois“ Alexander was threatened with deportation to Siberia. But with the German occupation from 1 July 1941 onwards, an even greater disaster began for the family.

Following the German invasion

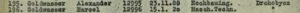

Immediately after the German invasion, a pogrom in Drohobycz, tolerated by the Wehrmacht, raged in Drohobycz, which was mainly perpetrated by incited Ukrainians as revenge against the „Jewish Bolsheviks“. Jews became outlawed, could be hunted, tortured and forced to do any kind of work. From July to the end of October 1941 Alexander Goldwasser had to work as a construction expert for the gendarmerie platoon stationed in Drohobycz. In the meantime, the German military administration had been replaced by a „civilian“ occupation administration and a department „Labour Deployment for Jews“ had been set up at the Employment Office. On 22.11.1941 about 250 sick and disabled Jews were summoned by the employment office and shot in the forest of Bronica, a few kilometres from the town. Being able to work, having a job and demonstrating qualifications required by the occupying forces became essential for survival. It was not difficult for Alexander as an engineer – from November 1941 he was assigned to work at the State Sawmills, which operated five or six sawmills. But now another problem threatened him: Dr. Nitsche, the head of the labour department of the governor of the district of Galicia, had announced on 20.9.1941 that all Jews from the age of 14 to 60 were subject to compulsory labour. Alexander Goldwasser, however, was approaching the age of sixty and would soon be among the superfluous „old people“ who were threatened with extermination. Therefore Alexander changed his date of birth – from 23.1.1883 to 23.11.1888.

In March 1942 he was assigned to Keramische Werke, also known as Klinker-Zement and Dachowczarnia. The Jews who had a job were pulled out of the ghetto in autumn 1942 and barracked in camps: Alexander Goldwasser, who until then had been allowed to live privately with his family in the ghetto, had to move to the labour camp of the Keramische Werke, which consisted of Wehrmacht barracks for the between 850 and 1,000 workers. We know from daughter Dola that in the summer of 1942, as a student, she took part in a rehabilitation course at the Jewish hospital in Drohobycz and worked and slept at the Hyrawka garden farm set up by the German chief of regional agriculture Eberhard Helmrich; son Marcel worked as a carpenter in the sawmill I (Hyrawka) and stayed overnight at his work site. Once a week the family was allowed to visit their father in the camp.

Starting in May 1943, after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Himmler urged that the extermination of the Jews be completed soon. The SS and police leader of Galicia, Katzmann, then gave Helmrich the order to hand over 50 of his 90 Jews with an R-passport to the forced labour camp of the Keramische Werke: one of them was Marcel Goldwasser, who thus joined his father in the same camp. (The Hyrawka camp was liquidated in June 1943 – Helmrich had previously managed to accommodate further Jews from the garden farm at the South Refinery and in a Carpathian Oil car repair shop)

Forced labour camps Keramische Werke and Karpathen Oil

The time spent together by father and son at the Keramische Werke lasted only briefly – until 25 August 1943, a Wednesday. Himmler had already given the instruction on 22.7.1943 that all Jewish forced labourers should also be „pulled out“ of armament factories, i.e. destroyed. Only the Karpathen-Öl AG had succeeded in obtaining a special permit for its Jewish skilled workers. Theobald Thier, Fritz Katzmann’s successor as SS and police leader in Galicia, wanted to prove himself as a strong SS leader as soon as he took office: he did not care that Klinker-Zement had previously been classified as important for the war and that it belonged to the SS economic empire. At dawn, the Ceramics Works camp was surrounded by a large police force (security police, Drohobycz police, Russian and Baltic camp guards and Ukrainian police). The 900 or so inmates were escorted to the Drohobycz court building and then pressed into cells of up to 80 people. In the evening, SS-Untersturmführer Friedrich Hildebrand – commander of the forced labour camps in the Drohobycz region since 1 August 1943 – appeared and read out the names of about 90 people who had been designated for the Karpathen-Öl AG labour camp in Drohobycz. Hildebrand recognised Alexander Goldwasser: he had been introduced to him by Minkus, his predecessor as camp commander. When Hildebrand saw Alexander Goldwasser, he separated him, as he did with his son Marcel, who had a student card from the Technical University of Lemberg. Those selected were taken to the forced labour camp Drohobycz of the Karpathen-Öl AG: there Hildebrand, with the help of the Jewish labour deployment leader Weintraub, selected about forty „superfluous“ workers of the Karpathen-Öl AG, mostly women, for „compensation“. „The group of ’superfluous‘ Jewish workers was led to the camp gate, where the defendant [Hildebrand] handed them over to the SS members who were standing by and who brought them to the Drohobycz prison to join the Jewish people who were being held there. The next morning, these innocent Jewish people were loaded onto trucks, driven to the forest near Bronica and all shot.” (Judgment of the Bremen jury court, 6.5.1953, p. 68). The shootings in the Bronica forest were commanded by Gabriel, the „Judenreferent“ of the Gestapo Drohobycz. Among those murdered were Regina and Dola Goldwasser, Alexander’s wife and daughter. Only Alexander and his son Marcel were still alive.

Father and son tried to stay together. The lists of Jewish employees and workers employed by the Karpathen-Öl, which the management had to deliver regularly, include Alexander Goldwasser as a graduate civil engineer and Marcel Goldwasser as a technical draughtsman in the refinery East and Technical Management. After the removal of all the Jewish forced labourers of the Carpathian oil, the management of the refinery in Drohobycz sent a list of the 47 engineers, chemists, inventors and specialists who were particularly missing to the head office in Lviv: Alexander Goldwasser was named as a special engineer in the construction office for the design of the new plant of the Galician refineries, and Marcel Goldwasser as a special technical draughtsman for designs of the new plants. It was of no use, however: on 13 April 1944 the forced labour camps of Karpathen-Öl AG in Boryslaw and Drohobycz were surrounded by SS and police units and all those who could be caught were driven into railway wagons.

From Plaszów to Brünnlitz

On 14 April, the 1,022 Jewish forced labourers of the Carpathian Oil – 245 women and 777 men – arrived at the Krakow-Plaszów concentration camp. The camp commander Hildebrand had promised them work in Carpathian Oil plants in western Galicia, and the management had expected this too until shortly before. The horror of the „Carpathian Jews“ was accordingly great when their train slowly entered the concentration camp: a huge camp surrounded by an electrically charged double barbed-wire fence with a moat, 13 watchtowers with MP riflemen and searchlights, a guard team of Trawniki and SS; loud dog barking and commandos roaring from megaphones received them. Camp leader was the brutal SS-Untersturmführer Amon Göth, whose morning pleasures included shooting at working prisoners. Most prisoners had to work for the SS company Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke (DAW). A subcamp of the concentration camp was located at Lipowa Street in Krakow: there, tinware and later only ammunition was produced for Oskar Schindler’s Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik (DEF).

As the front came closer, plans and lists for the evacuation of the camp were feverishly drawn up, including the lists for the Schindler factory in Brünnlitz. One of the typists typing such lists was Hilde Berger, who had also arrived in Plaszów by the transport on 14 April. When she realised that the Schindler list obviously offered greater chances of survival, she wrote herself and some names she knew from Boryslaw and Drohobycz on the Schindler list; other names were given by Josef Feiner. She could only add a few names of Jews who did not work for Schindler without attracting attention. Finally, twelve names of Jews of the transport from Drohobycz and Boryslaw were on the list – whether they were all inserted by Hilde Berger or some got on the list by other means is not known. Even the name Ignacy Klinghoffer (Igor Kling) from Boryslaw, who had arrived by another transport, was finally on the list.

In October 1944 the male „Schindler Jews“ were taken to the Groß-Rosen concentration camp for quarantine. Schindler had to bribe more SS officials until the journey finally led to Oskar Schindler’s factory in Brünnlitz, in Czechia.

After liberation: where to go?

On May 9, 1945, the Schindler Jews were liberated: none of them had been beaten or murdered in Brünnlitz during this period, although the SS guards had always threatened to do so. While the others rescued left in the following weeks, Alexander and Marcel stayed in Brünnlitz: 62-year-old Alexander was traumatised and ill. In October, father and son arrived in the US zone in Germany and passed through several DP camps: in Cham, Schwandorf, Traunstein, Bad Wörishofen. They did not want to return to Poland, where they had lost everything, but their declared goal, leaving for Palestine, was not possible for a long time. While Marcel resumed his studies, Alexander took care of the professional training of young Jewish survivors who wanted to emigrate. From 1946 to 1948 he was director of the Institute of WORLD ORT (Organisation – Reconstruction – Training) in Munich, a non-governmental organisation which had already been founded in Russia in 1880 as a society for craft and agricultural work for Jews. In the post-war years, many people willing to emigrate were trained by the ORT, especially in Bavaria. Alexander ended this activity at the age of 65.

In 1950 a former Jewish forced labourer in Bremen recognised the former camp commander Hildebrand in the open street and reported him to the police: Hildebrand was arrested and a trial against him was prepared. On 19 May 1951, Alexander and Marcel Goldwasser were questioned by the examining judge Dr. Penning in Munich as witnesses in this first Hildebrand trial. Alexander Goldwasser described how he unsuccessfully tried to get his wife and daughter spared through the refinery director Höchsmann and the camp commander Hildebrand. He was promised this, but not fulfilled. In the trial against Hildebrand in 1953, these statements were not taken into account. After his testimony Alexander Goldwasser collapsed – he refrained from reading his testimony again. Both witnesses were sworn in at their request, as they were about to emigrate. From 1952 onwards, father and son lived in Tel Aviv.

short biography Alexander Goldwasser

Twelve survivors: From Plaszow to Brünnlitz

Main Sources:

Arolsen Archives (AA), ITS documents on Alexander and Marcel Goldwasser

Entry list KL Plaszow 14.4.1944 from Drohobycz and Boryslaw, AA, 1.1.19.1/2059000/ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives

shindler’s list, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_von_Schindlerjuden#K

Testimonies of Alexander and Marcel Goldwasser, in: Hildebrand-Prozess, 1.2.7.8,/9039400/ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives

Urteil Schwurgericht Bremen gegen Friedrich Hildebrand, 6.5.1953, AA, 1.2.7.8/9039500/ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives

Andrea Übelhack, Briefe aus einem vergessenen Koffer. http://www.judentum.net/kultur/schindler.htm

Pohl, Dieter, „Schindler, Oskar“ in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 22 (2005), S. 791-792 [Online-Version]; URL: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118755102.html#ndbcontent

Shmuel Rothenberg, Drohobycz between the Two World Wars; https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/drohobycz/dro095.html

Schreibe einen Kommentar