Youth years

Ernst Lederer was born in Mannheim on 9 February 1913 as the son of Georg Lederer and his wife Nanette, née Sulzberger. Georg Lederer ran a beer wholesaling business in Feudenheim, which was incorporated by the city of Mannheim in 1910. Mannheim was an industrial and working-class city, while the industry-free suburb of Feudenheim was a popular place to live for wealthy citizens, but also for workers. There was a Jewish community, with a synagogue built in 1813 and a Jewish cemetery. Ernst Lederer grew up in Feudenheim, first attending four grades of primary school and then secondary school. Afterwards he went to the Tulla-Oberrealschule in Mannheim until his Abitur at Easter 1932. His further path was unclear, as he felt no particular inclination towards a specific profession or course of study. For six months he worked in his father’s beer depot, after which he listlessly began a commercial apprenticeship in the sales department of Olny Deutsche Benzin- und Petroleum G.m.b.H. in Mannheim.

Ernst Lederer was born in Mannheim on 9 February 1913 as the son of Georg Lederer and his wife Nanette, née Sulzberger. Georg Lederer ran a beer wholesaling business in Feudenheim, which was incorporated by the city of Mannheim in 1910. Mannheim was an industrial and working-class city, while the industry-free suburb of Feudenheim was a popular place to live for wealthy citizens, but also for workers. There was a Jewish community, with a synagogue built in 1813 and a Jewish cemetery. Ernst Lederer grew up in Feudenheim, first attending four grades of primary school and then secondary school. Afterwards he went to the Tulla-Oberrealschule in Mannheim until his Abitur at Easter 1932. His further path was unclear, as he felt no particular inclination towards a specific profession or course of study. For six months he worked in his father’s beer depot, after which he listlessly began a commercial apprenticeship in the sales department of Olny Deutsche Benzin- und Petroleum G.m.b.H. in Mannheim.

After Adolf Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933, the National Socialists seized power within a few months: the Reichstag was dissolved, democratic parties were banned and many members of parliament were put into concentration camps and tortured without trial. This rapid, violent path into dictatorship impressed Ernst Lederer mightily: although he had not been active in the Hitler Youth or any other Nazi organisation, he now saw the chance for a quick career with the Nazis – without the arduous path of vocational training, where he would have to be subordinate, and without studying. It was his decision – no one had forced him.

read more >

The Pact with the Devil

On 1 May 1933, Ernst Lederer joined the NSDAP and the SS (SS member no. 100 545, SS-Sturm 4/II/32 in Mannheim). Six months later, he applied to the SS (Politische Bereitschaften Württembergs) and received a permanent position with the SS as early as 15 December 1933. He broke off his commercial training. First he joined the SS Hundreds in Ellwangen. In October 1934 he was then ordered to a Führeranwärter course and in April 1935 to the SS Führer School in Bad Tölz. He did not stand out for his special achievements („I passed the final examination at the Führer School“, self-written curriculum vitae 1936), but for his outwardly demonstrated special radicalism. After an eight-week course for platoon leaders in Dachau, he was promoted to SS-Untersturmführer. He was then transferred to the SS-Oberabschnitt Nord (Stettin) in Schwerin. In September 1936 he submitted his engagement and marriage application with Susanne Groß to the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (RuSHA). The bride was Catholic, Ernst Lederer described himself as „German-believing“, and the wedding was to take place as a „marriage consecration by the SS“. In 1937 he was called to the SD-Hauptamt (Abwehr) in Berlin in May, where he met his mentor and advocate, SS-Brigadeführer and Police Major General Heinz Jost. From May 1938, Lederer headed a sub-department under him (Referat III/214/3). When Heinz Jost became Chief of Civil Administration at Army High Command 3 (C.d.Z. at AOK 3) after the invasion of Poland in September, he made Lederer his adjudant. During the occupation in Poland, Lederer had „particularly proven himself“ – he was certified as suitable to be a department head in Berlin. During this time, the SD-Hauptamt Auswärtiges under Heinz Jost was transferred to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) as Department VI.

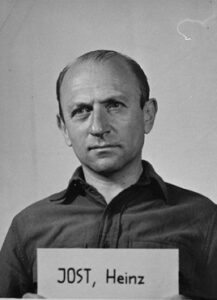

Excursus: SS Brigadier General Heinz Jost

Heinrich (Heinz) Maria Karl Jost was born on 9 July 1904 in Holzhausen, the son of a pharmacist. His path to the Nazis was not predetermined. At the age of 17, Jost joined the Young German Order. The Jungdeutscher Orden was the largest national-liberal association in the Weimar Republic – its name referred to the historical „Teutonic Order“ from the Middle Ages. The organisation was nationalist, but not monarchist or radical right-wing. The association explicitly advocated reconciliation with France. What paved Heinz Jost’s later path to the Nazis, however, was the association’s elitist attitude and its pronounced anti-Semitism: from 1922, Jews could no longer become members. In 1923, he passed the Abitur at the Gymnasium in Bensheim and then studied law in Gießen and Munich (graduating as a trainee lawyer in May 1927).

He joined the NSDAP in February 1928 (membership number 75,946) and the SA in 1929. At that time it was still completely uncertain whether the Nazis would ever come to power. Jost soon built up a regional power base and network. From 1930 onwards, he practised as an independent lawyer on the one hand and at the same time acted as a local group leader of the NSDAP in Biblis, Lorsch and Bensheim. His early commitment paid off for him directly after the seizure of power: in March 1933 he became police chief in Worms and from September police director in Gießen, where Werner Best recruited him for the Security Service (SD). From July 1934, he worked full-time in Himmler’s SD as head of department III (Abwehr). In 1938 he took part in the occupation of the Sudetenland as head of the Einsatzgruppe Dresden. In August 1939, he procured the Polish uniforms needed for the faked attack on the radio station in Gliwice (the faked attack served as a reason for the war against Poland). In the newly created Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), Jost then headed Office VI (SD Abroad) from 1939 to early 1942. From March to September 1942 he was head of Einsatzgruppe A, at the same time commander of the Security Police and SD (BdS) in the Reich Commissariat Ostland in Riga, and thus largely responsible for the Holocaust in the Baltic States and Belarus. Because of his association with the defeated Heydrich rival Best, however, his career came to an abrupt end: in autumn 1942 he was transferred to the Ostministerium and from April 1944 was assigned to the Waffen-SS. Himmler ordered his retirement from the SS in January 1945; at the age of 40, Jost became an early retiree.

He joined the NSDAP in February 1928 (membership number 75,946) and the SA in 1929. At that time it was still completely uncertain whether the Nazis would ever come to power. Jost soon built up a regional power base and network. From 1930 onwards, he practised as an independent lawyer on the one hand and at the same time acted as a local group leader of the NSDAP in Biblis, Lorsch and Bensheim. His early commitment paid off for him directly after the seizure of power: in March 1933 he became police chief in Worms and from September police director in Gießen, where Werner Best recruited him for the Security Service (SD). From July 1934, he worked full-time in Himmler’s SD as head of department III (Abwehr). In 1938 he took part in the occupation of the Sudetenland as head of the Einsatzgruppe Dresden. In August 1939, he procured the Polish uniforms needed for the faked attack on the radio station in Gliwice (the faked attack served as a reason for the war against Poland). In the newly created Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), Jost then headed Office VI (SD Abroad) from 1939 to early 1942. From March to September 1942 he was head of Einsatzgruppe A, at the same time commander of the Security Police and SD (BdS) in the Reich Commissariat Ostland in Riga, and thus largely responsible for the Holocaust in the Baltic States and Belarus. Because of his association with the defeated Heydrich rival Best, however, his career came to an abrupt end: in autumn 1942 he was transferred to the Ostministerium and from April 1944 was assigned to the Waffen-SS. Himmler ordered his retirement from the SS in January 1945; at the age of 40, Jost became an early retiree.

After the war, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Einsatzgruppen trial on 10 April 1948, which was reduced to ten years in 1951. Only a few months later he was released from the Landsberg war criminals‘ prison. Afterwards he worked as a lawyer for a real estate company in Düsseldorf and, camouflaged by his activity at the real estate company, worked for the Federal Intelligence Service (BND) from 1961 at the latest. The war criminal Jost died unmolested on 12 November 1964 in Bensheim.

Company commander of the barracked gendarmerie in Drohobycz

Lederer’s career continued: the SS promoted him to Hauptsturmführer (11/1939) and in July 1940 he was appointed Captain of Police. At that time, he had led a „police hunting platoon“ in the Generalgouvernement for several months. In autumn 1941 Lederer then became commander of the 1st Company of the Reserve Police Battalion 133 in Drohobycz. Because such units were barracked like soldiers, they are also called troop police.

The reserve police battalion was motorised and therefore had a large radius of action. Initially, Police Battalion 133 had been set up in the Nuremberg area – recruited at first from a few professional police officers and from young volunteers who came forward because they were exempted from military service and believed they could do their service close to their home towns. This soon proved to be an illusion: the battalion was deployed in the Generalgouvernement and from October 1941 in the new district of Galicia behind the front, to fight resistance and mass murder Jews and „Gypsies“ (Sinti and Roma). Mostly somewhat older reservists were called up and filled up the battalion.

The battalion consisted of three companies – the battalion commander was Lieutenant Colonel Gustav Englisch. He was based with his staff and the 2nd and 3rd companies in Stanislau (today Ivano-Frankivsk). The 1st Company under Lederer was barracked in Drohobycz, where the SiPo (Security Police) also had a branch („Border Police Commissariat“). But unlike the SiPo Drohobycz, which was responsible for the Drohobycz region (the three districts of Drohobycz, Sambor and Stryj), the 1st Company of Battalion 133, as a mobile unit, was regularly commanded to operations also outside this district – to Stanislau and Kolomea, to Lviv, and especially also to the north of the district of Galicia, to Rawa-Ruska and Kamionka-Strumilowa (Security District North). Conversely, the 2nd and 3rd companies of the battalion from Stanislau were deployed not only in the south and east of the district, but also in the Drohobycz region (especially in the Stryj and Skole area) – in accordance with the logistical planning for larger murder operations. In September 1942, the police was reorganised: Battalion 133 was renamed Battalion II of SS Police Regiment 24 – the 1st Company / Btl. 133 became the 5th Company of this regiment (LASH Abt. 352.4, Bd. 1734, Bl. 1138f.). Since it is the same company, the old designation is retained in this text for the sake of simplicity.

In contrast to stationary police units such as the Security Police, the Protective Police and the Gendarmerie, where victims were confronted with these police units for a longer period of time and surviving eyewitnesses were able to identify individual perpetrators, this was rarely possible with mobile units such as the Police Battalion 133 with its constantly changing locations: „Unknown men appeared, carried out their murderous task, and left“. (Browning_EN, p. XVII). Without the use of these mobile murder squads of police officers, the Holocaust in Galicia could not have been carried out so quickly and comprehensively: „The police battalions were of enormous importance to the occupation regime because of their manpower. Generally called upon for guard duties, they became outright Jew-killing units as early as October 1941.“ (Pohl, p. 91).

Bloodstains of the 1st Company

The following overview lists some murder actions from the period from October 1941 to the end of 1942 in which Lederer was certainly or very probably involved with the 1st Company of Police Battalion 133 (hereafter abbreviated to: 1st Kp./133). Wolfgang Curilla has compiled an incomplete list of the mass murders in which the troop police were involved; certainly the 1st Kp./133 was involved in a number of other murder actions that Curilla mentions, in those that he has overlooked in his listing, as well as in others that never became known due to the lack of investigations and witnesses: since about 97% of the Jews in the district of Galicia were murdered, there were no survivors left for many places and actions who could have reported.

6.10.1941: After consultation with the SSPF Galicia, Katzmann, execution of 2,000 Jews from Nadworna, with the participation of the Pol.-Btl. 133 (participation of the 1st Company probable, but not proven with certainty). Sources a.o.: Sandkühler, p. 150; Browning, Entfesselung, p. 502; Curilla, p. 772).

12.10.1941: During Bloody Sunday at the Jewish cemetery in Stanislau, the Security Police (SiPo), the Protective Police, the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police and members of the Reserve Pol.-Btl. 133 murdered at least 10,000 Jews – the largest massacre in Galicia up to that time (Herbert, p. 66 names the 1st and 2nd Companies of Pol.-Btl. 133. This makes participation in the mass murder in Nadworna probable. Browning, Entfesselung, p. 502, Curilla, p. 772).

22.11.1941: extermination of approx. 250 Jews from Drohobycz by troop police and SiPo in the Bronica forest (Sandkühler, p. 318; Curilla, p. 773)

25.3.1942: Deportation of 1,000 to 1,500 Jews from Drohobycz to the Belzec extermination camp (Sandkühler, p. 324; Kuwalek, p. 337; LASH Bl. 1142)

27.7.1942 Deportation of 5,000 Jews from the Rawa Ruska area, with the participation of the 1st Kp./Btl. 133 (Curilla, p. 773)

23.7.-1.8.1942: Before and after this death transport, killing of 64 Jews and 5 Jewish „partisan helpers“ as well as beggars, „gypsies“, vagrants and others by the 1st Kp./133 (Curilla, p. 773; Westermann p. 61). From summer 1942 to spring 1943, the 1st Kp./133 had the task of „cleansing“ the area of Rawa Ruska and Kamionka-Strumilowa and shot numerous escaping Jews during this time – at least four times they each took 20 or more Jews from the prison of Rawa Ruska and shot them in the forest (Pohl, p. 275; Curilla, p. 774)

4-8.8.1942: actions in Sambor (about 5,500 Jews), Boryslaw (about 5,750 Jews) and Drohobycz (estimated at about 4,000 Jews) – in total about 15,000 Jews – deported to Belzec (Sandkühler, pp. 334-341; Kuwalek, p. 343 f.; according to Sandkühler, p. 336, the 1st Company was not yet involved in the action in Sambor, but was involved in the following actions in Boryslaw and Drohobycz; LASH Bl. 1142 f.).

September 1942: participation in the shooting of about 2,000 Jews near Kamionka-Strumilowa (Curilla, p. 776)

21-24 October 1942: deportation of almost 3,500 Jews from Drohobycz, Sambor, Boryslaw and Stryj. See Ernst Lederer’s „Aussiedlungsbericht“ and many other sources (e.g. Pohl, p. 240; Geldmacher, pp. 109-111; Sandkühler, p. 356).

Autumn 1942 (until mid-December): The increasing certainty that the railway transports would not end in a labour camp but in the Belzec extermination camp led to more and more escape attempts by the desperate inmates. The cattle cars were locked, additionally boarded up and the ventilation slits secured with barbed wire. Nevertheless, prisoners repeatedly attempted to break out: most were shot by the guards as they jumped out. The others were hunted down by gendarmerie platoons and the 1st Kp./133 – the latter alone shot up to 90 escapees a week (Pohl, p. 294).

28.10.1942: Deportation from Kamionka-Strumilowa „On 28.10.42 1,023 Jews were deported from Kamionka-Strumilowa. Kam.-Strum. is thus free of Jews“ (operational report 5./Pol.-Rgt. 24 of 31.10.42, quoted from Pohl, p. 240).

11.12.1942: Deportation of 2,500 Jews from Rawa Ruska to the Belzec extermination camp. „During the reporting period, the Einsatzkdo. [Einsatzkommando] was deployed to resettle Jews in Rawa Ruska. 750 Jews who were in hiding after the resettlement were dealt with according to orders.“ (Report 12.12.1942 Sicherungsbezirk Nord, Einsatzkommando, 5./Pol.-Regt. 24 – i.e. the former 1. Kp./133 under Lederer. quoted from Pohl, p. 242. „Dealt with according to orders“ means shooting on the spot. Cf. also Curilla p. 776)

Units of the troop police like the 1st Company thus took part in countless ghetto clearings, shootings and deportations. They often cordoned off the execution sites or guarded prisoner transports, while the mass killings were carried out mainly by firing squads of the SiPo and Ukrainian militia. Volunteers from the troop police were also able to murder in the large-scale operations planned by the SSPF, but above all in the countless smaller operations. Ambitious troop leaders like Lederer tried to distinguish themselves by having a particularly large number of „their men“ participate.

Using the example of the Reserve Police Battalion 101, Browning distinguished several groupings: „a nucleus of increasingly enthusiastic killers who volunteered for the firing squads and ‚Jew hunts‘; a larger group of policemen who performed as shooters and ghetto clearers when assigned but who did not seek opportunities to kill …; and a small group (less than 20 per cent) of refusers and evaders“ (Browning_EN, p. 167). This is true, as we know from further research, for almost all police units – including the 1st Kp/133. Nothing happened to the „non-shooters“ except that they were scorned and mobbed as weaklings, cowards and shirkers by fanatical officers like Lederer.

Lederer’s Resettlement Report

Lederer had made himself unpopular with subordinates and superiors – his position was no longer uncontroversial. On 25.10.1942 he attempted a liberation strike by sending a secret letter to the commander of the Ordnungspolizei (KdO) in the district of Galicia, Walter von Soosten. In the letter he reported on the „Judenaussiedlung“ from 21 to 24 October 1942 in the Drohobycz region. According to his information, 1,179 Jews from Drohobycz, 460 Jews from Sambor, 1,020 Jews from Boryslaw and 800 Jews from Stryj were „resettled“, i.e. herded onto the death train to Belzec.

Lederer had made himself unpopular with subordinates and superiors – his position was no longer uncontroversial. On 25.10.1942 he attempted a liberation strike by sending a secret letter to the commander of the Ordnungspolizei (KdO) in the district of Galicia, Walter von Soosten. In the letter he reported on the „Judenaussiedlung“ from 21 to 24 October 1942 in the Drohobycz region. According to his information, 1,179 Jews from Drohobycz, 460 Jews from Sambor, 1,020 Jews from Boryslaw and 800 Jews from Stryj were „resettled“, i.e. herded onto the death train to Belzec.

This letter is one of the documents of the Nazi occupation that openly describes an extermination operation in the district of Galicia and is therefore often quoted in publications about the Holocaust in Galicia. Moreover, the letter says a lot about the author himself: about Ernst Lederer, chief of the 5th Company of the Police Regiment 24 (i.e. the former 1st Kp./133). He addressed the letter to the Chief of the Order Police in Galicia, Soosten – for the attention of the Chief of the II Battalion in Stanislau, his immediate superior: it was thus to remain internal within the Order Police. Lederer wanted to make an impression on his superior – that was the real purpose. Lederer would not have been authorised to address the letter to other units such as the security police and the SSPF, but strangely enough they did not appear at all in the report itself: who else was involved and who was in command? Only the platoon of the Breslau Guard Battalion, which was deployed later, was mentioned by Lederer, thus giving the impression that this resettlement action was carried out exclusively by troop police. Lederer then suggested „ongoing local actions in which the returning Jews are arrested“. In Stryj and Sambor this had already been practised with success. What Lederer wants to sell here as his own idea had already been done exactly this way before.

In August 1942, the Führer of the SS and Police (SSPF) in the district of Galicia, Fritz Katzmann, had assigned SS-Obersturmführer Robert Gschwendtner to lead the resettlement in the districts of Sambor, Stryj and Drohobycz. „The Drohobycz Border Police Commissariat [i.e. the SiPo and SD Drohobycz under Hans Block], the mobile police under Lederer as well as the gendarmerie were informed by orders from their commanders; the three district captains … had been prepared for the coming ‚expulsions'“ (Sandkühler, p. 334). After the resettlement 4.8.42 in Sambor and the surrounding area (150 Jews „unfit for work“ shot, 600 selected as forced labourers for the Lemberg camp, about 5,500 Jews locked in wagons and transported to Belzec), Gschwendtner had arrived in Boryslaw on 6.8.1942 with his „resettlement commission“ and had had the Wolanka ghetto district surrounded early in the morning. Since the news of the brutal action in Sambor had already spread and many Boryslaw Jews had fled into the forests and hiding places, however, not as many Jews were caught as planned. Therefore, the action was stopped for the sake of appearances and the murdering troops continued to Drohobycz. Late in the evening, however, they returned to Boryslaw and rounded up Jews from all parts of the town. Since many Jews had returned from their hiding places in the meantime, the action was more successful this time: a total of 5,750 Jews were caught and transported to Belzec. Lederer with his 1st Company was there, but only as an auxiliary force – the decisions had been made by the Resettlement Commission under Gschwendtner. This procedure – to stop an action for the sake of appearances and then strike again later – was used several times in the following period, but could never become the general procedure for the expulsions: the police forces were simply too small to carry out actions at one place for several days and at the same time to be able to keep to the dates agreed with the Reichsbahn for the transports to the extermination camp. Lederer’s great „idea“ thus found no resonance with his superiors.

The End

Lederer no longer had any protection at this time: his mentor Jost had been sidelined and he himself had made himself unpopular with his arrogance and ruthlessness. In the spring of 1943, he was replaced as company commander in Drohobycz. The former Battalion 133 was transferred to Central Russia and replaced by the Res.-Pol. Batl. 307 (I. Btl./SS-Pol.Rgt. 23) under Major Herbert Wieczorek (Sandkühler, p. 82). Ledererer was tried several times: as early as 1942 before the SS and Police Court in Krakow, in June 1943 before a court in Minsk and finally in January 1944 before the Main SS Court in Berlin. He was accused of high-handedness („quick-tempered nature“) – the exact charges are not known.

Ernst Lederer had to „prove himself“ at the front in Belarus. In July 1944, he was reported missing in action near Borrissow. His short career as a Nazi perpetrator of violence ended at the age of 31.

Sources Lederer / Police Regiment 133:

Browning, Christopher: Ganz normale Männer. Das Reserve-Polizeibataillon 101 und die „Endlösung“ in Polen. Hamburg 2013. [Cited as Browning]

Browning, Christopher: Ordinary Men. Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Revised edition, 2017 (Kindle) [Cited as Browning_EN]

Browning, Christopher: Die Entfesselung der „Endlösung“, Berlin 2006 (esp.: chapter 8.2, section „Ostgalizien“, pp. 499-507) [Cited as Browning, Entfesselung]

Curilla, Wolfgang: Die deutsche Ordnungspolizei und der Holocaust, Paderborn 2006 (especially: seventh section, „45th East Galicia“, pp. 770-789)

Geldmacher, Thomas: „Wir als Wiener waren ja bei der Bevölkerung beliebt“, Wien 2002

Herbert, Ulrich: Vernichtungspolitik. Neue Fragen und Antworten. In: Herbert (ed.), Nationalsozialistische Vernichtungspolitik 1939-1945, Frankfurt/Main 1998

Pohl, Dieter: Nationalsozialistische Judenverfolgung in Ostgalizien 1941-1944. München 1997

Sandkühler, Thomas: „Endlösung” in Galizien. Bonn 1996

Westermann, Edward B.: „Ordinary Men“ or „Ideological Soldiers“?. In: German Studies Review, 1998, S. 41-68

Most important archive materials:

Arolsen Archives, Bad Arolsen: (File 9034800) Aussiedlungsbericht Drohobycz, 25.10.1942 (2 pages).

Federal Archives (BArch), Berlin (BDC): R 9361-II/115716; R 9361-III/539778

DALO, Lviv, Ukraine: R 1933-1-15, sheet 2

LASH (Landesarchiv Schleswig-Holstein), Schleswig, Dept. 352.4 Lübeck, Vol. 1734

Sources Heinz Jost:

Klee, Ernst: Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Frankfurt 2012, p. 290

Wildt, Michael: Generation of the Unconditional. Hamburg 2003

Federal Archives, Berlin (BDC): R 9361-II/476400, R 9361-III/88310, R 9361-III/533804

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinz_Jost

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinz_Jost